The Widening Appeal of Private Placements & Infrastructure Debt

Illiquid asset classes like private placements and infrastructure debt can offer investors incremental risk-adjusted returns, as well as a number of other compelling competitive advantages.

Institutional investors are increasingly considering investments in illiquid private markets, including private placements and infrastructure debt. For insurance companies and pension funds, in particular, these markets can offer a number of potential advantages, ranging from an illiquidity premium over public markets to enhanced diversification, risk protection, and positive asset-liability matching attributes.

The Defining Attributes

Private Placements

Private placements are essentially notes and loans sold only to qualified institutional buyers (QIBS); they do not have to be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Historically an investment grade market, private placements span a range of categories beyond traditional corporates, from REITs, sports-related transactions and financials to more esoteric products such as structured finance, credit-tenant lease transactions and aviation deals. A decade ago, the private placements market consisted primarily of small and medium sized companies seeking to raise capital to supplement bank financing. That is no longer the case, with many large companies globally choosing to access the private placement market as a means of gaining another source of capital to achieve their financing objectives.

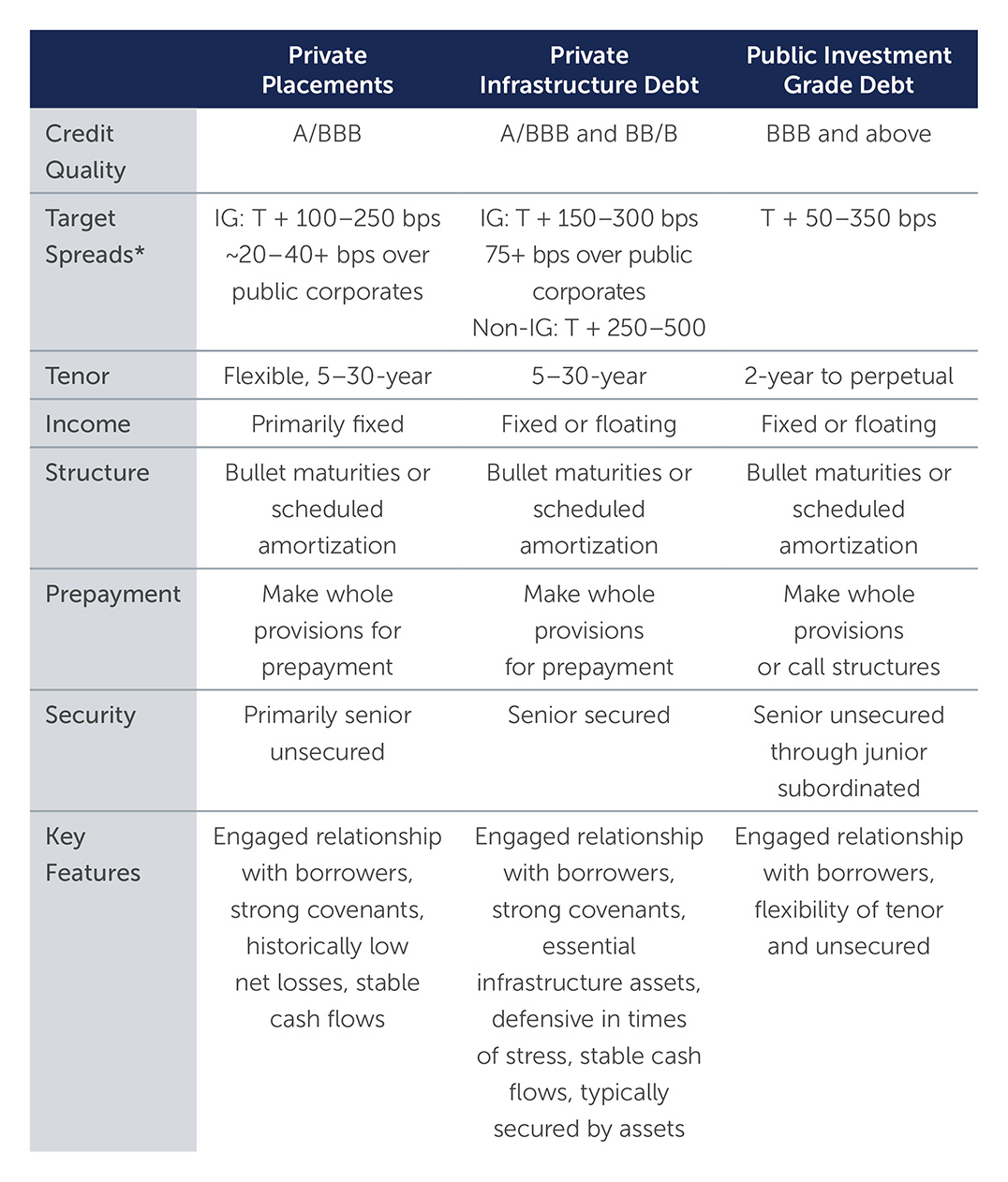

Figure 1: Key Characteristics of Private Placements and Private Infrastructure Debt vs. Public Bonds

Source: Barings. As of April 30, 2022.

Infrastructure Debt

The definition of infrastructure debt is broad and can vary significantly among asset managers, banks and investors. At Barings, our definition centers on the type of asset generating the cash flow, rather than the specific financing structure. We primarily focus on essential assets that meet key social and economic needs and that have the potential to generate stable, long-term cash flows for investors.

The infrastructure debt market was once almost exclusively the domain of banks. In the past, institutional investors who did gain access to infrastructure assets generally did so through allocations to private equity funds. The key events that set change in motion were the Global Financial Crisis and the European debt crisis. As banks looked to reduce their liquidity and pulled back sharply as a funding source, institutional asset managers were able to step in and fill the gap—particularly in the U.S., where banks still act as arrangers but are typically not involved in lending to the same extent as in Europe.

22-2112613